Chapter 1.1. What is a Mod?

A mod (also known as an extension, hack, or plugin) is a piece of software that modifies another piece of software. Usually in games, this is done through the use of a mod loader; something that, well, loads mods. Some games, like Friday Night Funkin and Skyrim have built-in support for loading mods, as well as built-in interfaces for working with mods, which make modding very easy and simple.

Geometry Dash, unfortunately, does not have any built-in mod support. However, using very clever methods such as DLL injection and hooking, we can create an external mod loader. This does come with some disadvantages like the lack of a stable API (meaning it’s not guaranteed to work between versions), but it also comes with some huge advantages, such as fully unrestricted access (which might also be seen as a huge disadvantage, depending on who and when you ask). A mod can do basically anything, within the limits of computer hardware.

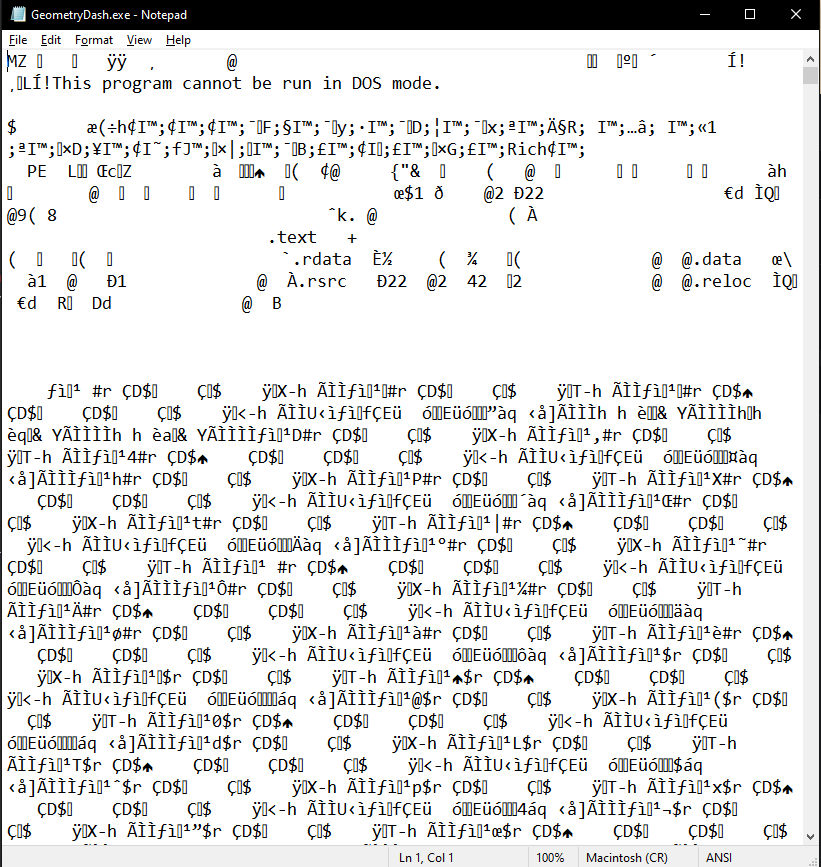

But how exactly does a mod work? The actual executable file for Geometry Dash that you have installed on your computer is what is known as an executable binary program. If you open the game’s executable with a text editor, you will see a bunch of random-looking characters. This is, in fact, the game’s code; however it is not its source code. This is binary code, the raw low-level instructions your CPU executes. If we had the game’s source code, we could create a fork of it and add built-in mod loader support. However, as Geometry Dash is closed-source, we have to deal with modifying the binary code.

Modifying binary code is a bit difficult, however, as it is not meant to be for humans; binary code is strictly for computers, and as such it is unreadable and unmodifiable for a human. Binary code is also platform-specific: a mod written purely in binary would only work on one platform, and could not be ported over to others without fully rewriting the entire mod from the ground up.

As a historical curiosity, it should be noted that mods used to be written fully in binary. Or, more accurately, they were written in assembly, which is a (somewhat) human-readable form of binary. However, to make it very clear, no sane person does this anymore. Working with binary code directly is nowadays only done in rare cases, which will be explained in Chapter 1.2.

But what’s the alternative? We can make modding much easier by knowing two facts:

- Binary code is produced through compilation.

- Geometry Dash is written in C++.

Compilation is the process of turning source code into binary code. While we can’t modify GD’s binary code easily, we can write our own source code in C++ and compile it into compatible binary code. Knowing what language GD was made in is vitally important, as not all binary code is equal. Some programming languages such as Rust produce wildly different binary code from C++, and while it is technically compatible, it is much easier to work with a C++ game using C++. (Some modders, however, are working on making Rust usable for modding!) Writing our mods in a higher-level language like C++ also makes porting much easier; C++ can be compiled to compatible machine code on all the platforms GD is available on. This does come with multiple caveats though, however those are left for a later chapter.

What all of this means is if we write our mod in C++ and then find some way to make GD run the compiled binary code of it, then we have unlocked a path to modding! And luckily, we know how to make GD load extra code: binary injection.

Almost every platform GD is on has some sort of dynamic library support. On Windows, these are known as .DLL files; on Mac, they’re .DYLIBs; on Android, they’re .SO files. A dynamic library is like a binary executable, but they have one special property: other executables can load them. This is usually done through address tables and the such; these are much too complicated for the purposes of this tutorial, and the specifics are also platform-dependant and modern modloaders use proxy DLLs instead. As such, how binary injection works in detail will not be explained here. All you have to take away is that we have methods to make GD load a dynamic library, and that acts as our entry point to modding the game.

ℹ️ There is one platform that doesn’t have dynamic library support: iOS (unless jailbroken). Modding on iOS without jailbreaking requires basically baking all the mods you want into a premodified game, like iCreate has done, but a general mod loader like Geode will likely never see iOS support unless some major changes to the OS happen first.

📗 If you are interested in learning more about binary injection, the Wikipedia article on DLL injection is a pretty good place to start.

Usually, the first custom dynamic library we make GD load is a mod loader; that is, a mod whose purpose is to load other mods. This is because the methods we use for injection are not easily scalable, but once we have our one library running, we can invent much simpler ways of loading more of them. For example, on Windows, loading a library from another library that you control is as simple as calling the LoadLibrary function. This can also be done an arbitary number of times within our initial library, so we can for example automatically find all the .DLL files in some directory and load them. This is how old 2.1 mod loaders such as Mega Hack v7 used to work: they would search for all of the .dll files in a predefined folder like extensions and call LoadLibrary on them.

At this point, we’ve gotten our library up and running, and are ready to start writing some code. However, now we enter a new problem: how do we actually do things?